Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B Construction Photos

Page 16

A Mixed Bag of Images, and Stories to go With Them

(Original Scan)

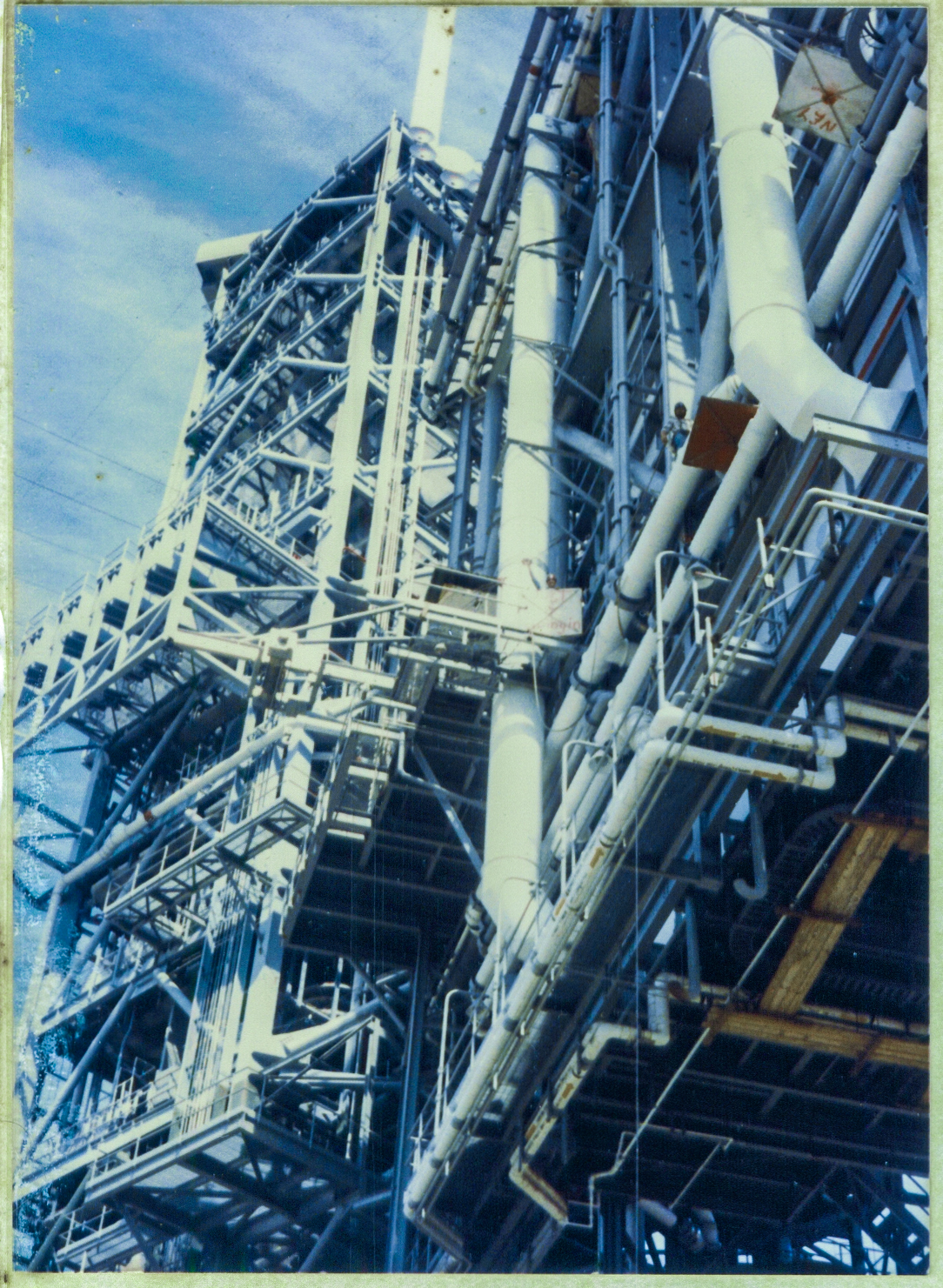

Top left is the back of the towers, taken from pad deck level behind the RSS. Look closely and you'll see an ironworker gazing back down at you, and another waving to you. You may also notice little squares of wood, sticking out from the steel here and there. These are "floats" and are sheets of plywood, four feet square, stiffened with 2x4's, tied to the structure with heavy rope wherever there's work to be done. Step off on to one, and it will move underneath you. Look over the side, and it's a sheer drop of a hundred feet or more. Totally exposed to the wind, the sun, the heat, and the cold. If you work in a cubicle, or behind a counter, or perhaps somewhere else, and do not like the environment, maybe take a shot at working someplace where they tie floats to the steel and see if you like that better.

Top right is Jack Petty.

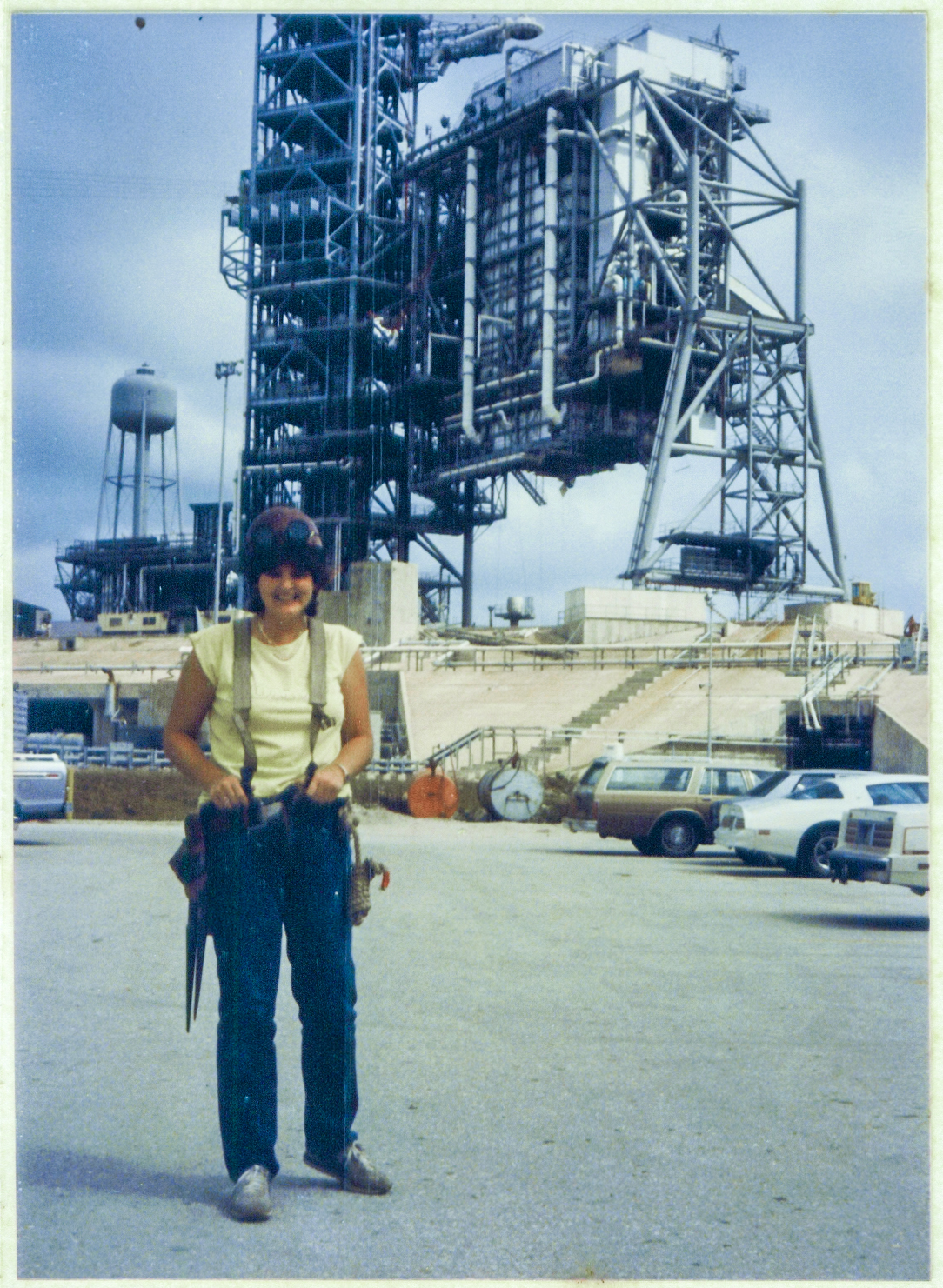

Bottom left is Wade Ivey's daughter, Tammy, goofing around in the parking lot by our field trailer, with the towers behind her.

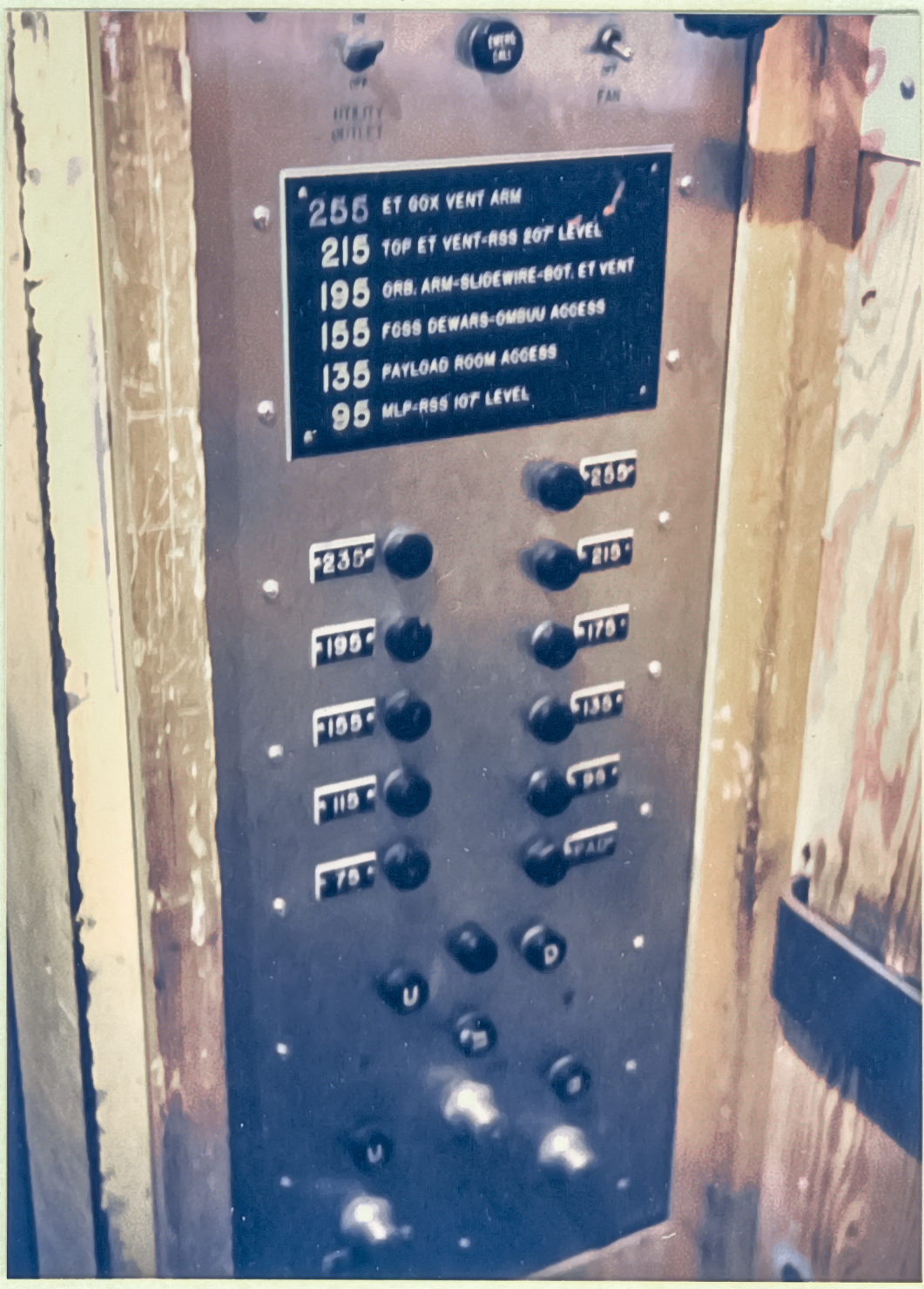

Bottom right is the button panel inside the FSS elevator.

Additional commentary below the image.

Top Left:

(Full-size)

Back of the towers.

Give it two or three hundred percent zoom if and when, please, there is, as usual, stuff going on.

The back side of the RSS is to the right, with a pair of large white air ducts running vertically most of the way to the top, and farther away, at a different angle, is the FSS.

I count four floats on the back of the RSS, and two ironworkers, one each near both of the lowest floats. On the left, you're getting a raised arm and a wave, and on the right, you're just being looked at. The work was strenuous, dangerous, and long, but there was always time for a few lighter moments, such as this one. That's Gene Lockamy on the left with his arm in the air, balancing the float he's holding on to edgewise, supported by the beam it's resting on top of. Yeah, stop and consider that one for a moment, please. It's not enough that you have to put your fucking life on the line, traversing narrow splinters of high steel on a regular basis, in and of itself. No. That's not enough. While you're traversing the splinters, you also get to wrestle large awkward pieces of equipment, off-balance, over the sides of deathly precipices, into and out of hard-to-access, out-of-the-way, difficult locations, while you're doing it.

Go get a nice heavy piece of three-quarter inch plywood and cut it into a four-foot square. Go grab something that's four-foot square, right now. Feel the awkward as you try to move around with it in the nice safe confines of the room you're in. Now cut some two-by-fours and screw them to the perimeter of your four-foot-square piece of plywood to stiffen it up some. And some one-inch rope. Not too much, but enough, and it weighs, so you have to count that in, too. And not only does it weigh, it also snags and trips if you're not minding yourself with it. Drill holes in the corners and thread the rope through them in the shape of an 'X' like you see in this picture.

Now go take your nice new float, half-dragging it, half-carrying it by hand as best you can, and get up on the roof of the tallest building in your neighborhood, or even the whole town. Even if you live in Chicago. Maybe even especially if you live in Chicago. You're walking with it. You're carrying it. And it's awkward. And you're out there in the wind. Can't forget the fucking wind now, can we? You're sitting inside somewhere, reading this, and you're not even thinking about the goddamned wind. But it's a little different up on the iron. The wind never stops blowing, and the higher you go, the harder it blows. Anybody that's ever been up there can tell you all about the goddamned wind. And your float makes for a pretty good sail, and it can, and it will, catch the wind that never stops blowing, and you better be ready for that shit, ok? And now you get to walk right over to the very edge of the building you're standing on top of. And I mean the very edge, keeping in mind just how good you've got it, not having to balance on the dreadfully-narrow top flange of an I-beam that may only be four inches in width, or sometimes even less, and instead you have the entire parking lot of the building's whole goddamned roof beneath the fear-soaked soles of your boots.

And now you get to wrestle your float down over the goddamned side of the building's roof, maybe even with some overhang to deal with while you're at it, and then tie your float off nice and secure to whatever might be there that you can throw some rope around, and then work your ass right on over the side of the building, out over an empty void that's seamlessly lined with certain death down on the very bottom of things, and then put all your weight on your float, feel it swing and sway as the ropes creak and tighten, and your weight shifts here and there, and then let go of the building and trust your life to it, and then grab your tools and equipment, maybe some welding leads or something, and then pull your welding hood down and get your sorry ass to work.

Respect.

In spray paint, scrawled on the bottom of the float in the far top right corner of the image, it says "Ivey" and this sort of thing was done with most all of the tools and equipment, down to and including things that were too small to put actual words on, which would instead just get a hit with a company's "color" and I'm pretty sure Ivey's "color" was orange, but it's been a long time, right? Orange is nice and easy to spot. I also recall green, yellow, and blue, among other things, but I could not give you any help at all with the particulars of who had what. Wires and hoses would get hit with a simple swatch of Ivey Orange, and larger things like floats would get the full word, and this was done as a measure to minimize job-site theft, which, although it never got out of hand, was something to be kept in mind for items that could be casually picked up and walked away with, and this too was one of the ways that the different crafts sniped at each other as an ongoing background thing.

But Gene Lockamy's float does not say "Ivey" on its underside. Sometimes, a wry sense of humor could creep into things, and in this case, it says, "Just Swingin" although it's very hard to make out all of the letters, and if you hadn't already known it, you would never in a lifetime have guessed it.

This shot was taken before the framing for the new PCR Anteroom (security checkpoint, air-shower, bunny suits in sealed plastic bags), which you had to pass through to enter the main area of the Payload Changeout Room itself, had been hung on the existing iron of the RSS. Yet another change order. Yet another realization in cold steel and hard dollars that their initial premises were none too good, and would not get the job done, as-is. The old anteroom was a cramped affair, stuffed up against the back left corner of the PCR exterior wall, with barely enough room for a functionary to sit at a small desk, check your badge to make sure you had the good numbers on it that were required for access beyond that desk, verify that you had your bunny suit (which at that time, over on A Pad [B Pad not being active yet] you had to go down inside of the concrete hill into the Pad Terminal Connection Room and requisition the bunny suit), let you through the small closet of an air shower, into yet another space with benches where you put the bunny suit over your normal clothing, and thence on through, finally, the last door that opened directly into the PCR floor.

Whether or not this picture was taken at the very beginning of the installation of the new anteroom, which was a capacious thing that ran along the entire back side of the RSS, I cannot say. But three of the four floats visible would be at the correct locations and elevation for tying the floor framing steel for the new anteroom to the existing steel of the Rotating Service Structure. The material for the new anteroom may or may not have already been laying over on the other side of things in the shakeout yard, ready (more or less) to be lifted into place and tied to the existing structure of the RSS, so who knows?

In the bottom left corner of the image, you can see the platform framing for the RBUS, which was located on the FSS Hinge Column Struts that tied the FSS to the Hinge Column, and from which, on the other side, the Centaur porch would have protruded out toward the flame trench. The RBUS itself is nowhere to be seen.

Almost exactly in the middle of the image, extending on out on the left-hand side, you can see the framing for the emergency egress slidewire baskets (which there were only five of, back at this time) access platform on the back side of the FSS. Zoom in really close, and all five of the slidewires can be seen extending out of frame, above the complexity of the platform framing, to the left. We furnished and installed the whole thing, and once we were done, of course it had to be functionally tested.

Astronauts, after all, would be in those baskets, fleeing for their lives subsequent to something awful developing with their fully-fueled, insanely-explosive, and incomprehensibly-dangerous rocket ship, trying to get the hell out of there, as far as possible as fast as possible, in the fast-fading seconds before the rocket ship blew itself clear to hell, killing everyone so unfortunate as to still remain in the general vicinity of it in the process. So the damn thing had to work. I always thought it was a quite a bit less-than-optimal system, but it was all they had, and fortunately, they never had to use it in a real-world contingency situation.

Anyway, back to the functional test, I lobbied hard and long with anyone and everyone, from NASA on down, for literal months, to be allowed to ride in one of the sonofabitches, ostensibly as the on-site representative for the firm that furnished and installed the system, but in truth, just to go for a ride in the fucking thing, come functional test day. But I was rebuffed at every turn, and when that day came, the baskets were loaded with sandbags to simulate the weight of the crew, and cut loose, unoccupied. I watched from right out in front of our field trailer as the baskets slowly moved away from the FSS, flying more or less in formation, down the slidewires, with the sounds of the pulleys that the baskets hung beneath first whirring, then whining, then squealing, higher and higher and higher in pitch as the baskets picked up speed, going downhill. By the time they got to the nomex nets that braked them, down in the safety bunker area, they were moving pretty damn fast, and that sound has stayed with me for a lifetime. And the feeling of being pissed off because I wasn't allowed to go for a ride in the fucking things has stayed, too. Oh well. Win some, lose some.

Look closely at the bottom right corner (as viewed in this image) of the side of the slidewire baskets access platform facing away from the FSS, and it appears as if there is an I-beam connected to that corner, extending to the right, and down at a bit of an angle, partially blocked along its length by a bit of a contraption, the shaded lower side of which can be seen, before that beam extends on and disappears into the complexity of steel on the RSS, below and a fair bit left of Gene Lockamy, standing there with upraised hand, balancing his float on its edge. But that I-beam is not connected to anything on the FSS, and it's just an accident of perspective that makes it look like it is. Structural steel can be very confusing in that regards. Really gotta look at the stuff, to see what's what, and where's where. Go find this beam, dammit, there's a story that goes with it, and the contraption, which is in fact a large wire-rope drum-hoist with its steel frame and the long cylinder of its drum running perpendicular to the direction of that I-beam that it's hanging from, which is in fact the monorail beam that the small (And of course we know all about "small" now, don't we?) trolley which supports the hoist runs back and forth on.

Really, go find this crap. Zoom in, dig around, and find it. It's confusing, but if you're zoomed in somewhere above two-hundred percent, you should be able to pick it up. The end of the hoist drum closest to us as we view it is a square thing, with a kind of round "button" protruding just a little bit farther in our direction. Take note of the longness and the thinness of that hoist drum. For some reason, they did not want the wire rope to wrap around the drum of this hoist over itself, and instead spec'd out a drum that was so long that the wire rope could spool around it from one end to the other without ever wrapping around on top of itself. A fair amount of trouble was gone to, to get this thing this way, and I really could not tell you what the deal was, or why this particular hoist had to be this way.

And, in truth, it wasn't just this particular hoist. There was a whole set of them, sprinkled around in different locations on the RSS, with monorail beams extending out beyond the envelope of the RSS, that they could use to pick up large, heavy, awkward objects, and bring them directly to this or that particular location, without having to worry about the impossibilities of threading things through the labyrinth of steel, elsewhere. Just roll the hoist to the outboard end of its monorail beam, lower the hook to the ground, hook on, lift the load up off the ground with the hoist till it's up in the air where it needs to be, pull the hoist inboard along the monorail till it was above the RSS platform framing where you wanted it, and let the load down right where you needed it.

I finally found a pair of the monorails they spec'd out for them, just beneath the main floor framing at the 125' elevation on the RSS, but there's more of them than that. Look close at the linked image, and you'll see some words associated with it, and although it's no-doubt a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy, and barely legible, it would appear as if the monorail in question is an S12 x 31.8 "Standard" rolled steel shape, and is hung just below the APU Servicing Platform, which is another name for the 125' elevation floor framing steel.

For some reason, the set of demo drawings I'm being forced to use in lieu of the actual erection drawings (one day I'll find a way to get hold of them, I swear), is missing the RSS 135' framing plan view, and that's a shame, 'cause there's a whole world of informative stuff on that level, which is the main floor level of the whole RSS. Ah well, so it must be.

Ok. Fine. Why are you belaboring this thing, MacLaren?

Good question.

Please note that our hoist drum is sitting outboard of the RSS envelope. Outboard of all that welter of other steel that makes up our RSS. Platforms, diagonal bracing, stairs, cable trays, pipe supports, walls, ducts, wires, you name it. No end of stuff. Mechanical, electrical, structural, who the fuck knows. Right now, the hoist is happy as a little clam could ever be, sitting out there in splendid isolation, away from all that confusion of stuff farther inboard.

And, although you cannot see any of them, every last one of the rest of that group of hoists which we furnished and installed, were also in their outboard positions, sprinkled invisibly amongst the steel of the RSS.

And how, you might ask, might I know such a thing?

Another good question.

I know this, because at the time this photograph was taken, none, as in not one, of these hoists actually worked and we were embroiled in a battle with NASA over them, and NASA was attempting to cause us to remove every single one of them from the RSS, at our own expense of, if memory serves, over eighty thousand dollars for the full set of them, and replace them with the exact same make and model of hoist, from the same manufacturer, with the same capabilities, and the same everything with one single exception. The replacement hoists needed to have drums that ran parallel, not perpendicular to their supporting monorail beams.

Just that one little detail. One eency weency little bitty detail.

Why?

Yet another good question.

Well, you see, it turns out that the wise NASA engineers who very carefully, and very specifically, spec'd out hoists with drums that ran perpendicular to their monorail support beams, failed to take in to account all of that "Platforms, diagonal bracing, stairs, cable trays, pipe supports, walls, ducts, wires, you name it" that the hoists would be rolled in toward, when it came time to place their loads upon the decking of whatever RSS platform they needed to deposit that load upon, and in fact, the poor hoists never had a chance, because their nice long drums, protruding well away from the line of the monorail beam above them on both sides, would smash into god knows what, long before the damn hoist was anywhere near where it needed to be in order to let its load down on to the deck plates or steel bar grating where it needed to be placed.

The hoist drums had to be clocked around parallel with the orientation of their supporting monorail beams to keep them from sticking out too far on both sides, or otherwise they would interfere with existing elements of the RSS, and be completely blocked from further travel toward their intended destinations inboard on the RSS upon encountering the first interference (and there was more than one, and sometimes many more, along the length of each and every monorail), thus rendering them completely unusable.

And so, the NASA engineers being the NASA engineers they were, they immediately attempted to push the full cost, materials and labor, as well as offering no schedule relief, onto us, claiming it was all our fault.

Whatta bunch of swell guys, huh?

With friends like these.....

And so, despite the fact that every single hoist was clearly, consistently, and precisely shown on every single drawing and rendering of them, as well as being specifically spec'd out with perpendicular drums in every instance, that charming bunch of fuckwits, assholes, and thieves worked mightily to hide their own mistake by attempting to foist it off on Ivey Steel.

Are we beginning to detect a pattern in these stories yet? North Piping Bridge? KSC-STD-C-0001? And now the Monorail Hoists?

Yes indeed, boys and girls, there really is a pattern.

These fucks were trying to hurt us and I'll be goddamned if I've ever been able to figure out why? WHY?

And this ain't the half of it, kids.

There's more.

And you'll never know. You'll never know the half of it.

So we fought 'em like the dogs they were, and in the end we beat them and they had to pay for the whole thing, time, material, and labor, as well as admit to their own stupidity, in a very public way. But it took a surprising amount of time and effort to do so. They just dug in on it, and would not let go. Until we beat them into submission.

But why? Why? Why must people and organizations be this way?

I'm sure I'll never know.

\\\

Addendum March 7, 2020: And lo and behold, after all this time, all these words, and all this digging. While researching a completely separate conundrum (monorail hoists! again, but somewhere else this time, up underneath the RCS Room), I stumbled upon THIS drawing, from 1976. Which means, without the slightest doubt whatsoever, that the whole enterprise, from beginning to end, as regards their attempts to push this off on us, cost, schedule, all of it, was a criminal cover-up from the very outset. Somewhere, somebody fucked up, and they knew it, but instead of being honorable about owning up to their own fuckup, they took the dishonorable road, and tried very hard indeed to break this one off in our asses. But it didn't work. We broke it off in their asses instead. Buncha fucking liars and thieves. Buncha fucking goddamned low-life crooks. Fuckem. Fuckemall.

///

Top Right: (Full-size)

Jack Petty, Briel Rhame Poynter and Houser tech rep, standing in front of the door that led to his end of the BRPH field trailer, where he worked, and where they kept the all the drawings, specifications, records, and everything else. Jack was structural, but they had mechanical and electrical in there too, and I worked with those people as well, some of whom were Good, and some of whom were..... not good. Over the years, I paid too many visits to that trailer to count. It was over at the other end of the parking lot, to the west, heading away from the pad itself, a short walk from our own field trailer.

Up the stairs, open the door, and immediately to your right, in the northeast end of the trailer, you'd find Jack's desk, butt up against the wall you see there extending to the right, out of frame, with a window above it.

On either side of the desk, no-frills metal shelving in black and gray, lined with no end of books and thick binders filled with specifications, engineering data, vendor information, and all the rest of what's required to ride herd on the structural aspects of a project this size. Very similar to what surrounded my own desk, in my own field trailer.

Top of the desk strewn with no end of paper, mechanical pencils, clear tape dispenser, stapler, knick-knacks in the form of structural and/or engineering items, rulers, drawing templates for curves, shapes, symbols, you-name-it, books standing on end between thin metal book-holders, car keys maybe, badges, black spring clips for stacks of paper that had gotten a little too thick, and on and on and on. All of it very austere, very governmental-looking, without adornment of any kind, in government colors, with a government smell (which is real, by the way), trending toward military, but with much less of a "dress right dress" ambience.

Jack was the nucleus of this atom, and all of this stuff surrounded him as an electron probability cloud surrounds the proton at the center of a hydrogen atom. And, as with a real electron probability cloud, things might be found here or perhaps there and they could move, and even blink into and out of existence, much as an electron might when examined carefully by a physicist using a particle accellerator to do so.

Adjacent to the desk, a bunch of tall file cabinets, filled to brimming with documentation of all kinds, desk drawers filled to overflowing with still more of it, except for the shallow center "junk" drawer that could be pulled out above your lap as you sat in the chair, which overflowed with its own little ecosystem of highlight markers, no end of mechanical pencils and lead refills for them, pens of all sizes and colors, paper clips, spring binders, business cards, notes, tape refill rolls, perhaps a low-profile hole-punch or two, small personal items, and all the rest of the archeological detritus that limned the engineering life which was lived here.

Nearby, a drawing table. Big F-size drawings and somewhat smaller D-size drawings laying flat on the table, and rolled up like so much cordwood, laying on the shelf that ran beneath the large flat tilted top surface of the table, stacked on end, next to the table, laying down in stacks, here, there, everywhere. Hundreds of pounds of the stuff. T-square. Large clear rulers, finely-divided. Tracing paper, drawing supplies. Everything you'd need to produce anything from a simple sketch to a polished formal document destined for submission to NASA itself.

Everything was done by hand. There were no computers in use. No screens. No keyboards. There were no computers small enough to even fit in something as small as a field trailer. Electronic hand-held calculators were still placed under the heading of "New-fangled." Mechanical adding machines still existed, and were still used, for the purposes of grinding out the endless streams of number, numbers, numbers, that fueled the system and made it go.

Fluorescent lights overhead, bare-bones illumination.

Turn around to your left, after squaring up with Jack's desk, and the open expanse of the multiple field trailers, all tied together, all with their intervening walls removed, presented itself.

More desks. More people. More shelving. More file cabinets. More drawing tables. More documentation.

There's Pete Irby's desk, across from Jack's, against the north wall of the field trailer. Pete's mechanical, and I didn't work with him much, but we get along, and sometimes we did find ourselves working together when the worlds of structures and piping overlapped as must they occasionally do, and he's yet another no-nonsense kind of person that just wants to get things done and leave the bullshit to somebody else.

Pete marveled at the way Jack and I would move around on high steel, and related the tale of when he used to do engineering work that involved climbing around on the tops of large spherical storage tanks, until, after a time, the everpresent threat of the tank sloping ever-steeper away from him, drawing him onward to his doom in a fall if he even slightly misjudged his location and the steepness of the slope he was standing on, finally got to him and was causing him to have recurring nightmares that would wake him from a sound sleep in the wee hours of the morning, and at that point he said "The hell with it," and he swore to never again tempt fate in such a way, and very sensibly got the hell out of there and found work in other, much safer, places.

Across from Pete, heading west, still in the north end of things beneath the roof that spanned the large open space beneath it, Joe Pessaro's desk could be found. More of the same stuff, but different. Joe is electrical, and electrical stuff is subtly different from mechanical stuff, or structural stuff, or cost-accounting stuff, or any of the rest of the disciplines that must all come together to produce the colossal iron behemoth which was growing into the sky, beyond the far end of the parking lot.

And spreading off to the far walls of the large open space... more atoms. More nuclei. More electron probability clouds. More archeological detritus of the lives which were lived there.

And outside, up on high steel, lives were being lived there, too.

Jack shows up in a fair amount of these photographs, and that's because we found ourselves working together a lot, even though were on opposite sides of the house, me being a contractor, and him being the tech rep for the customer, but we worked exceedingly well together as a team, and solved no end of problems working as a team. Jack was refreshingly free of the bullshit that adhered to so very many other people we had to deal with out there, on both sides of the house. Ex-ironworker. Knew his shit backwards, forwards, and sideways. His approach was very similar to mine: What's the answer to this question? Find the answer. As quickly and as directly as possible, no matter where that might lead, no matter who the finger winds up pointing at as the source of the problem that caused the question to get asked in the first place. And then go and implement the goddamned answer in the most efficient manner that will further the aims of the program to build NASA a goddamned launch pad regardless of political, social, business, or any other pressure. I've already said it, but I'll say it again. He was a Good Man.

Bottom Left: (Full-size)

Wade Ivey's daughter, Tammy, goofing around and mugging for the camera dressed in an ironworker's toolbelt and hard hat. This photo was taken right out in front of our field trailer where my office was located. Whenever I walked outside into the parking lot and looked to the right, absent Tammy, this is what I saw.

Bottom Right: (Full-size)

FSS elevator, button panel. Lousy shot, ambient light, no flash, sloooow shutter, but take a gander at the labels next to those buttons.

You'll never see anything even remotely resembling it, anywhere else you might ever go, in your entire life.

255 ET GOX VENT ARM

215 TOP ET VENT - RSS 207' LEVEL

195 ORB. ARM - SLIDEWIRE - BOT. ET VENT

155 FCSS DEWARS - OMBUU ACCESS

135 PAYLOAD ROOM ACCESS

95 MLP - RSS 107' LEVEL

As if I needed any further reminding of the nature of the insanely amazing and fantastic place I'd fallen into by complete stupid unwarranted luck. But there it was anyway, every time I went up the tower.

Also, those elevations are all wrong. In the interests of reducing confusion when people went from A Pad to B Pad, the numbers in use for A were faithfully reproduced over on B. But the pad deck on B was five feet higher, so every one of those numbers is five feet too low. A small thing, to be sure, but a very real thing, too.

Return to 16streets.comACRONYMS LOOK-UP PAGEMaybe try to email me? |